When Localism isn’t Liberalism

“Community Politics” doesn’t mean local control of house building.

The Liberal Democrats really love local politics. There’s nothing a group of Lib Dem canvassers love more than trekking to an obscure council by-election or pointing angrily at potholes. It’s partly because we can win there, sure, but it’s also part of a long tradition of localism within liberal politics that now forms one of the key tenets of the party’s platform: local control.

In many cases local control is crucial. As liberals we believe that everyone knows best about their own life - certainly much better than the state does - and that people should be given every opportunity to reach their fullest potential and thrive. This applies similarly to local communities, who know much more about the problems they face and how to solve them than central government ever could. That’s why decisions should be devolved to the lowest feasible level to enable people to shape and control their own area.

This formula, pushing decision making and responsibility down towards devolved administrations and councils, is generally a good one. Greater local control should normally be fought for and welcomed. But, as a party, we pride ourselves on not sticking to rigid dogma: we evaluate policy positions on their merits. For every area where localism is the solution, there is one where it clearly isn’t.

Let’s take a really obvious policy example: defence. No one would argue that individual councils should have their own armed forces, or that councillors should have any control over military strategy - we all accept that this would be ridiculous - but we should analyse what core aspects of this policy area lead us to these conclusions.

Whilst every member of a local community is impacted by our national security, we accept that this interest cuts across council boundaries. We accept that the actions taken to defend people in Westminster impact those over the border in Camden. It would be ridiculous for one local area to “opt-out” of national security spending or to take a completely different geopolitical stance - it’s a problem of collective action across councils.

We have tools to decide questions like these, and chief among them is UK-wide democracy. Decision at this level does not imply we cede control, but instead that we recognise the constituency for this issue is broader than simply local. Just like the right level for control of bin collection is local, the right level for defence is national, or even super-national in some cases.

This argument is hardly rare in Lib Dem politics. Brexiteers spent the last five years arguing that making any decision in Brussels was an abnegation of “national sovereignty”, but those of us in the remain camp rightly pointed out that such pooling of power actually enhances our ability to tackle cross-national issues. We liberals are able in many realms to correctly identify the appropriate deliberative body.

Community politics

There is a fascinating document put out by the ALC1 in 1980 entitled "The Theory and Practice of Community Politics"2. This pamphlet sets out an entire approach to liberal politics focused on communities. The authors go to great lengths stressing that this is not only, nor even primarily, about geographic communities but instead a much more general concept. The effects of this document can be seen throughout Liberal (and later Liberal Democrat) policy and campaigning but we have forgotten any meaning of the term community beyond "local".

Community Politics gives us a fantastic framework through which we can analyse questions about what is the right place for questions to be decided. The authors argue strongly for communities that control their own destiny, devolving decisions to the level that makes the most sense, but today we seem to have decided that that is always a geographic area. Whilst localism is often a viable approximation for "true" community politics, there are plenty of cases when this is not true.

We have already seen that defence has a different community to bin collection, but Community Politics tells us to look at many other definitions of “community” for democratic control. The pamphlet argues that a union, or a workplace (for example) are communities that Liberals should consider equally to local areas when considering democratic devolution. Not every suggestion is right, or has stood the test of time, but the principle is as relevant now as ever.

Even restricting ourselves to a geographic lens, Community Politics can be used to justify (for example) a commitment to federalism, or strong regional government. Many policy areas do not work at a council level, but we see very different demands in different regions. Strategic transport needs in London are very different to those in Cardiff, or Birmingham or Yorkshire. These cannot be left to local councils — the thinking needs to be more “joined-up” than that — but national government is also too big to effectively deal with regional variation.

By asking ourselves “which community does a question impact?”, “who does this serve?”, we can often find the liberal approach we should take to democracy.

Housing

By and large power in the UK tends to be far too centralised, not diffuse. In so many cases wrestling power from Westminster results in better and more responsive decision making. But there is one key policy area where this is not the case. One where the Lib Dem obsession with “localism” gets in the way of both good policy and a commitment to liberalism: house building.

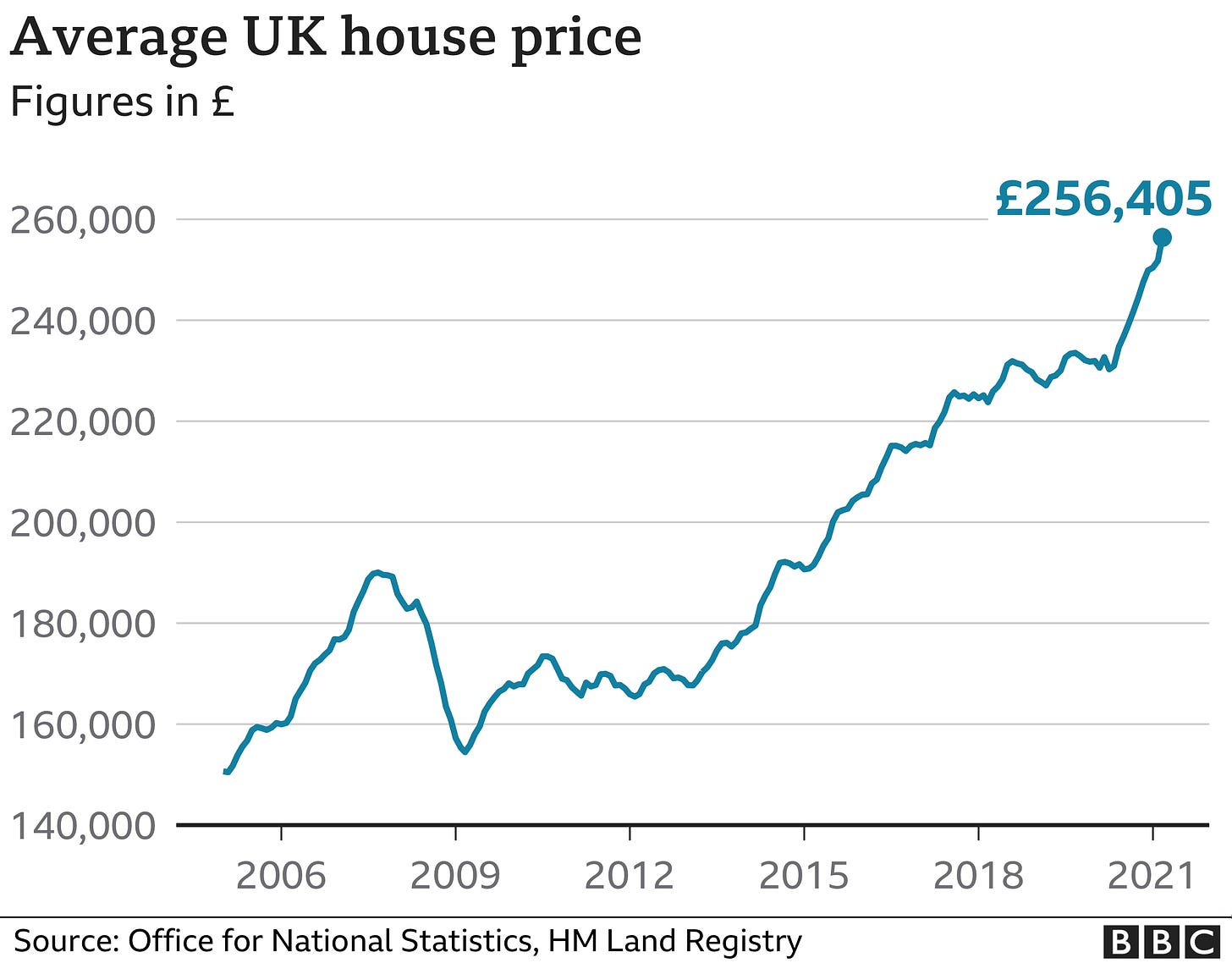

We need to build more houses, that’s just a fact. The Government estimates we need to build upwards of 300,0003 homes simply to keep up with demand let alone to tackle the skyrocketing prices we have seen across the country - especially in the South East.

As liberals, the housing crisis should disgust us. It is a denial of a core freedom - to live and work where you want. The Liberal Democrats purport to accept this, promising to build hundreds of thousands of new homes a year were we in power, but this commitment runs straight into the unstoppable political tenet that is "local control".

Localism cannot work for housebuilding because new development is not, by and large, for local residents. Nor should it be! By definition, expanding the housing stock of an area means letting new people move into it. The constituency, the group people affected by what and how much housing is built, is not limited to the people who already happen to live in the area but instead extends to people who participate in the UK property market - i.e. everyone (but especially young people who are the most likely to rent privately and move around).

Looking at this question through the lens of community politics is a way to see why this is. The community here is not a local one. Local residents are impacted, they’re a part of the community, they need to have a say, but they’re not the extent of the community. By only letting local residents have a say on new development we are excluding communities who are locked out of the housing market from the conversation.

Political Implications

We see this issue crop up time and again. We recently won a landslide victory in Chesham and Amersham fought mostly on the basis of local opposition to house building. Otherwise fantastic, liberal, council groups will oppose construction when it might impact their or their constituents' lives (or house prices!). NIMBYism is rife within the Lib Dems.

To an extent, it's not the councillors' fault. By the very nature of local politics representatives are chosen by those who already live in an area - not by those looking to move there. But that doesn't mean it has to be this way. Our party has vociferously (and now successfully) objected to increasingly meek Conservative planning reforms on the basis that it will "take away local control of the process", despite the fact that development is not a local issue that should be locally controlled, but a national one that affects people - especially young people - outside a council area as much if not more than those already resident.

Councillors do an admirable job. They donate huge amounts of time, passion and expertise to the pretty thankless job of making our communities better. If you do well as a councillor, the best you can hope for is no complaints. When it comes to housing we do our councillors a disservice by giving them control of such a poisoned chalice. Councillors who know — as the vast majority of Lib Dems do — that the housing crisis must be tackled are asked to choose between their constituents and new housing.

Let’s instead move this to a more apt level of control: national (or regional). Yes, it means that you will have less say in if someone builds flats near you, but it will also unlock huge numbers of new homes, decades of lost economic growth and save our councillors from having to straddle an unbridgeable divide.

Conclusion

Housing supply is a national issue. It affects every single one of us and we’re all paying the price for too little housing. Local control, whilst often admirable, in this case, is getting in the way of some of our most treasured freedoms. Liberals must remember that localism is not an end in and of itself but a tool for greater freedom. Where it gets in the way of that it should be abandoned in favour of policies that make people’s lives better.

So next time you hear that the so-and-so want to reduce local control of planning, instead of reflexively recoiling you can ask yourself: why should living somewhere let you control who can move there? Perhaps the answer will surprise you.

Association of Liberal Councillors, now ALDC

http://www.rosenstiel.co.uk/aldc/commpol.htm

https://www.centreforcities.org/housing/

"...why should living somewhere let you control who can move there? Perhaps the answer will surprise you."

Excellent.

Thanks for posting.